THE

WAYWARD DAUGHTER

OF JUDAH THE PRINCE

A philosopher's "Thelma and Louise"

set in the Roman Empire

Written by Douglas Lackey

Directed by Alexander Harrington

ABOUT

THE PLAY

|

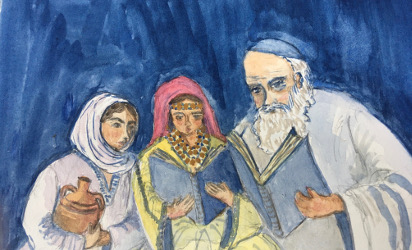

Study for the tale (watercolor

by Laura Layton). L-R: Sarah, Hannah, Judah. |

What’s a girl to do when her father is writing the most important book in the world? Help him, of course, until he throws her out of the house. The rift between the famous rabbi Judah (Judah ha-Nasi) and his daughter Hannah over an arranged marriage proposal tosses Hannah and her lover Sarah out across the turbulent waters of the Roman Empire. In her travels, her robust Judaism collides with Gnostics, pagans, and Christians. One misplaced word can mean the difference between life and death.

To playwright Douglas Lackey, the dichotomy of history and humanities versus the sciences is the central conflict of our civilization, as is the question of what is truth: is it particular or universal? So he dreamed up a play based on someone testing the primacy of inherited truth by challenging it with the rich brew of ideas "that were banging around in the late Second Century."

Hannah, the title character of "The Wayward Daughter of Judah the Prince," while vivid, is a historical mash-up. In the first half of the play, she is more or less pure invention, inspired by a thin historical record. (Sources relate that Judah and an unnamed daughter had a sharp disagreement over the slaughter of a Passover lamb, but there is no record that she ever left home.) In the second half, she is modeled on two historical philosophers.

As the play opens, Hannah is a caring daughter and able assistant to Judah in his theological writings, but she is caught between her devotion to her father and her dedication to intellectual study. After her love for Sarah, a Christian slave girl, is exposed, Hannah flees with the girl to Ephesus, where they meet Basilides, the leading philosopher of Gnosticism. There they narrowly avoid being drawn into Gnostic eroticism and ritual suicide. The oddity of Gnostic sexual practices is described in world literature, perhaps maliciously, by orthodox defenders of Christianity, notably Irenaeus of Lyon. This act draws upon these records and the Gnostic "Secret Gospel of John," which was discovered in Egypt in 1945 in a sealed jar buried in the desert.

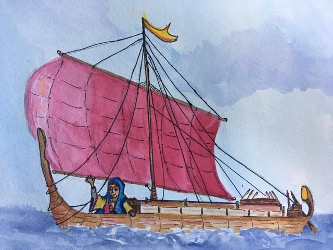

|

Hannah takes flight to Ephesus.

Watercolor by Laura Layton. |

In Act III, Hannah is modeled on Porphyry, author of the treatise "Against the Christians" who was assistant to Plotinus, the great pagan philosopher of late antiquity. Porphyry wrote the first philosophical defense of vegetarianism, "On Abstinence from Animal Food," which contains many references to Jewish law, leading to speculation that Porphyry was Jewish. Plotinus' philosophy, now called Neoplatonism, had a famous female adherent in the astronomer and mathematician Hypatia, who is the model for Hannah in Act IV. It is historically documented that Hypatia used menstrual cloths to defend herself against obtrusive men. This is recalled in a comic scene of the play, in which Hannah wards off menacing Gnostics using rags from the market stained with sheep's blood. Hypatia was killed in 415 AD by a Christian mob, almost certainly at the directive of Kyril, bishop of Alexandria. In the play, Kyril is an unmistakable symbol of the authoritarianism of the Church, a reflection on one aspect of Christianity of the time. Two other currents of Christian thought are offered in the play. The biblical essence of Christianity is represented in the beliefs of Sarah the slave girl. Gnostic Christianity is demonstrated in Basilides, the high priest of the sect.

Hannah's Jewish learning provides an effective foil against the ideologies she confronts in the play until she meets Plotinus in Rome. Then her devotion changes from her father's creed to aesthetics and empirical science. Her form of rebellion, triggered by spiritual hunger, is a repeating cultural phenomenon through the ages and has recently been dramatized in such iconic productions as "Unorthodox" and "Shtisel."

|

|

| |